How the USS cuts cannot be reversed

A critique of the UCU Left negotiators’ proposal to restore benefits by 1 April 2023

A blog has recently been created called “Reverse USS! — A website about how the USS pension cuts can be reversed”. Its first post, dated 14 December, contains a “suggested path from Deepa Driver & Marion Hersh” to the restoration of pension cuts by 1 April 2023, which is a year earlier than USS has said it might be possible to do so. The second post, dated 29 December, contains “an urgent motion for branches to consider”, which calls on the union’s HEC and negotiators to adopt their proposal “as the basis for negotiation, and push for its adoption by the USS JNC”.

The UCU Left grouping of the union has recently posted a statement on their website in favour of indefinite strike action from February, which makes the following reference to Driver’s and Hersh’s proposal:

Although they do not identify themselves as such in their 14 December post, Driver and Hersh are members of UCU Left and have in the past identified themselves as “UCU Left USS negotiators”.[*]

I have provided this piece of background information because I do not think their proposal makes sense other than as a post hoc attempt to justify UCU Left’s call for indefinite strike action from February over USS (as well as pay and conditions). It appears to be an attempt to create a casus belli against employers over USS by swiftly issuing a demand which they know employers will reject.

Were the union to issue such a demand that employers join them in their call to restore benefits by 1 April 2023, this would, however, backfire in spectacular fashion. This is because their proposal would collapse under the scrutiny it would then receive. It would soon become apparent that it is lacking in credibility for at least the following three reasons: (I) It is clear that USS would refuse to implement their proposed restoration by 1 April 2023 and that they would have sound reason for such refusal. (II) Restoring benefits on the basis of a positive funding position between full actuarial valuations would set a dangerous precedent for calls to cut benefits or increase contributions on the basis of a negative funding position between valuations. (III) Even if these changes could be implemented by 1 April 2023, they would not make members any better off than they could be made by changes that could be implemented by 1 April 2024.

I. Why USS would refuse to implement their proposal, and with good reason

The timings in their proposal lack credibility for the following reasons.

USS is required by law to conduct its next full actuarial valuation dated no later than 31 March 2023 (i.e., no more than three years beyond the date of the last full actuarial valuation). It will conduct a valuation so-dated.

USS could conduct their next full actuarial valuation at an earlier date. They could, for example, conduct one that reflects scheme funding as at 30 September or 31 December 2022.

Full actuarial valuations, however, take many months to complete, and there is no chance that USS would complete such a valuation in time to restore benefits as of 1 April 2023.

I presume that this is why Driver and Hersh have instead chosen to call on USS to restore benefits by 1 April 2023 on the basis of an interim monitoring updating of the 31 March 2020 actuarial valuation which is currently in force.

The model branch motion in fact opens with a reference to the 30 September 2022 quarterly monitoring updating of the 2020 valuation:

This UCU branch notes

1. That USS’s own estimate of its monitoring position in September 2022 projected a £5.4bn Defined Benefit (DB) surplus, continuing an upward trend.

USS, however, has noted that such quarterly monitoring updates fall short of a full actuarial valuation in the following respects:

Why isn’t the monitoring used as a valuation outcome?

The Financial Management Plan (FMP) monitoring reports track the funding position in respect of the current benefit structure in a relatively, and necessarily, crude approximation using a mechanistic approach. They only provide a snapshot of the scheme’s position at a given moment in time.

By contrast, an actuarial valuation requires much deeper and comprehensive analysis of long-term assumptions on a variety of factors, including inflation, interest rates, the outlook for future expected investment returns, mortality, the covenant position, and risk capacity, overlaid with judgement taken by the Trustee.

The FMP reports should therefore not be seen as an indicator of the likely outcome of an actuarial valuation. They reflect conditions between valuations on a pre-agreed methodology with limited judgement applied. They indicate — at best — the direction of travel, rather than the destination.

Hence, the proposal calls for the pushing through of a restoration of benefits effective 1 April 2023 on the basis of interim updated costings of the 31 March 2020 valuation that would soon be superseded by the costings of the next full actuarial valuation dated 31 March 2023.

On account of this fact, USS would have at least the following three compelling reasons to wait until after 1 April 2023 before implementing a full restoration of benefits:

1. They cannot now assume that funding conditions of a 31 March 2023 valuation would continue to justify the September or December 2022 costing of an updated 2020 valuation on which Driver’s and Hersh’s restoration would be based. Among other things, they lack clairvoyant knowledge that asset values and gilt yields as at 31 March 2023 will continue to justify such costings. Hence, they would have good ground to refuse to restore benefits effective 1 April 2023, knowing that this might soon need to be reversed by conflicting costings of an as at 31 March 2023 full actuarial valuation.

2. The updated costings of the 2020 valuation assume that the employer covenant is strong rather than ‘tending to strong’. As an aspect of the full 31 March 2023 actuarial valuation, USS will, however, be undertaking a new assessment of the strength of the covenant, starting in January. This will involve independent assessment from an outside auditor of covenant strength and will not be completed prior to 1 April 2023. Costings that presuppose a strong covenant would need to be revised — and probably very significantly — if such strength isn’t confirmed by this assessment and the covenant is downgraded to ‘tending to strong’. USS would rightly regard it as irresponsible to pre-judge the result of the covenant assessment in progress by pushing through changes effective 1 April 2023 that presuppose a strong covenant.

3. Given their previous public statements (including what I have quoted above) that a quarterly monitoring report provides a poor substitute for the more thorough and comprehensive analysis of a full actuarial valuation, USS would be hard pressed to justify, to the regulator, a sudden change of course in which they implement changes on the basis of such quarterly monitoring. The regulator is good at throwing past USS statements back in their face, and USS realises this.

One of the changes that Driver and Hersh call for would pose a special difficulty: their proposal that the DB/DC salary threshold be restored to c. £60k for future DB accrual, effective 1 April 2023. USS has declared, and with good reason, that this would count as a ‘listed change’ which requires a 60-day member consultation.

The model branch motion mentions the following:

there is a short time window before USS Joint Negotiating Committee (JNC) meets on 8 February 2023. This is a crucial meeting at which it would be possible to agree pension changes to take effect from the start of the new scheme year, 1 April 2023.

By the 8th of February, it would, however, be too late for JNC to agree an increase in the salary threshold for future accrual to take effect from 1 April 2023, since there are fewer than the required 60 days to conduct the statutory consultation between those dates. Even if an earlier emergency JNC meeting were called in January after the branch delegate and HEC meetings on the 10th and 12th of the month, that would still leave too little time for the preparation and notification required to launch a 60-day consultation and the steps that need to be taken after the consultation involving analysis of consultation feedback and implementation of results.

II. Hostage to fortune

As USS rightly points out, pushing through changes on the basis of positive funding position between the 2020 and the 2023 valuations would make members hostage to fortune if the funding position deteriorates between the 2023 and the next valuation:

· The precedent it could set may have less desirable consequences: The Pensions Regulator might reasonably expect the opposite to happen in future if the funding position deteriorated.

USS’s caveat is justified in the light of guidance from the regulator that “We expect trustees who have previously allowed for positive post-valuation experience to also consider any material negative post-valuation changes at future valuations”.

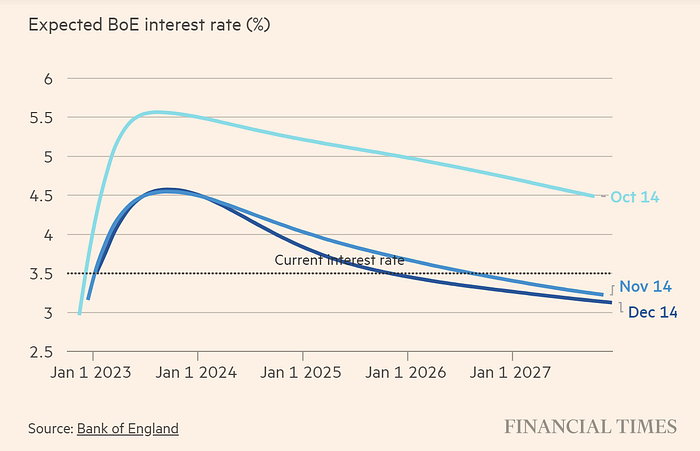

If, moreover, forecasts regarding inflation and the Bank of England interest rate turn out to be roughly accurate, scheme members would be especially vulnerable to such pressure arising in the aftermath of the 31 March 2023 valuation. It is on account of the recent rise in the interest rate and therefore gilt yields that the scheme is now much more well-funded than in past years by USS’s lights. But market expectations in recent months have consistently indicated that the interest rate will fall in 2024, 2025, and 2026 after peaking in 2023:

If such forecasts are roughly accurate, it would make sense to try to lock in a restoration of benefits at favourable costings based on a full actuarial valuation in March 2023, which can last for at least three further years even if gilt yields and/or asset values fall significantly in the meantime. Moreover, we’ve learned that lots of nasty, unanticipated things can happen between valuations. Hence, it would be good to be able to protect the anticipated positive position of the March 2023 valuation so that it carries us through to the next required valuation, in spite of monitored volatility in the meantime.

Our opportunistically trying to grab an upside interim valuation date to push through positive changes ahead of the March 2023 valuation would make it harder to ride through downside volatility in the future.

Like many others, I would maintain that this volatility arises from a flawed valuation methodology. But we now lack the means to force USS to adopt a different approach for this coming valuation, while also fast tracking the upshot of the valuation so that it will be possible to retrospectively and prospectively restore benefits effective 1 April 2024.

III. Nothing is gained by pushing through a restoration effective 1 April 2023 that cannot be gained via restoration effective 1 April 2024

Prospective and retrospective implementation of restoration of benefits effective 1 April 2023 achieves nothing that cannot be achieved via restoration effective 1 April 2024. This is because Scheme Rule 34A, entitled “Augmentation of Benefits”, makes clear that even those who retire between now and 1 April 2024 can have the benefit accrual that was cut from 1 April 2022 retroactively restored while they are a former rather than a current member.

For this reason, it is especially unclear why union members should be called upon to engage in indefinite strikes in the near future, to try to force an implementation of a prospective and retrospective restoration effective 1 April 2023 as opposed to 1 April 2024.

As I have indicated at the outset, I believe that the best explanation of their proposal is that it is a post hoc attempt to rationalise UCU Left’s call for indefinite strikes over USS from February. It comes across as an attempt to find a problem which does not exist, for which the solution is massive industrial action over USS at a time which objectively makes no sense (as I noted in a blog that I posted back in October). Members are poorly served by the false hopes to which this proposal gives rise. I draw attention now to its serious problems, in the hopes that adding to the debate at this critical juncture will put us back on the track of a realistic and attainable timetable whereby benefits are fully restored, both prospectively and retrospectively, by 1 April 2024, rather than within the next three months and two days.

Postscript added 1 January 2023

The model branch motion claims that “we cannot … wait until a new valuation, because…USS has had a consistent track record since 2011 in changing the valuation methodology which has created new projected deficits…”

Two responses:

1. USS is on record as stating that they will carry over the current valuation methodology (see, e.g., Mel Duffield’s presentation, starting at 1:55:50, and especially from 2:01) to make it possible to fast track implementation by 1 April 2024 of changes arising from the upcoming 2023 valuation.

2. If, however, contrary to what they have claimed, USS actually plans to disadvantage members by revising the 2023 valuation methodology for the worse, Driver’s and Hersh’s proposal to push through changes on the updated costings of the 2020 valuation fails to protect against USS and UUK’s reversing these improvements via the 2023 valuation which supersedes the 2020 valuation.

I’ve also posted four sequels to this blog post: (1) ‘An Achilles Heel of the “Reverse USS!” FAQs’, (2) ‘The absurd timetable of the Reverse USS! proposal’, (3) ‘Why the UCU Left negotiator proposal sets a dangerous precedent’, and (4) ‘Indefinite strikes are too much, too late, to restore the DC threshold by April’.

[*] When they posted that blog, Driver and Hersh were both UCU-appointed members of the Joint Negotiating Committee (JNC). Driver remains a JNC member. Hersh is now a UCU-appointed alternative to the JNC.